Beyond Biba, Beyond Fashion | Clothes on Film

Biba did things differently. It was a shopping revolution. If a Biba sales assistant approached a potential customer browsing and asked “Can I help you?” they would have been fired on the spot. Biba was unique. Topshop is not Biba.

Beyond Biba: A Portrait of Barbara Hulanicki (directed by Louis Price, 2009) is exactly that; a relatively short (56 minutes) but detailed look at a woman defined by the brand she created. This is a patient story, surprising in parts but mostly just enlightening. There is much to learn from this film, although it never feels as though you are being lectured.

The innovative fashion and lifestyle brand Biba was started by Barbara Hulanicki and her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon as a mail order boutique in 1964, expanding to four direct selling shops, all in London, all within easy walking distance of each other. In 1969 they opened an epic seven storey department store that sold almost everything. From A-line shift dresses and wellingtons to make-up and even Biba blend coffee.

Biba eventually closed its doors in 1975, a year after Barbara walked following internal disagreements with the majority company who had taken control. This was not the result of quality concerns over the admittedly inexpensive clothing (a common misconception), but rather Barbara and Fitz hoping to expand the Biba name ever further and needing help to do so. Corporate hit creative and the whole venture fell apart within months.

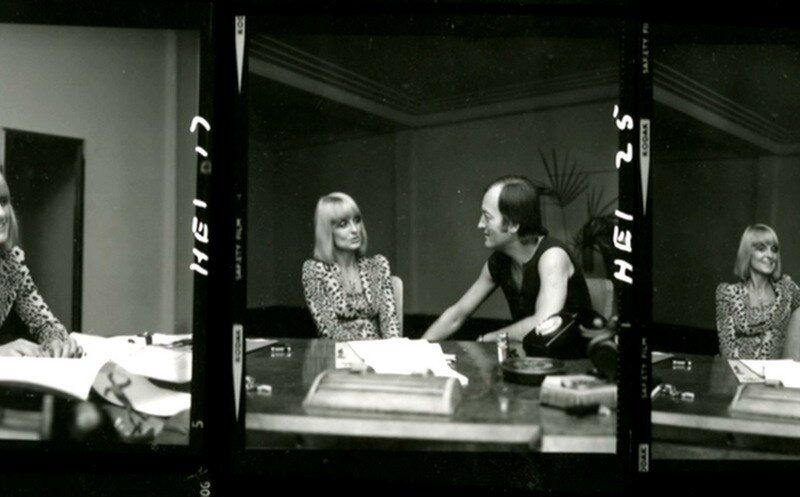

Barbara Hulanicki started her career as a fashion illustrator while Fitz cut his teeth in advertising (“rather badly” he states, charmingly, during some archive footage in the film). This ensured a perfect partnership; he handled the business side while Barbara concentrated on making the clothes. She lost Fitz to cancer in 1997 and now resides permanently in Miami, Florida as a successful interior designer, a key player in the area’s hotel regeneration during the last quarter of a century.

Born in Warsaw, Poland in 1936, Barbara came to London as a child following the death of her father by terrorists. Setting up Biba in her late twenties, she effectively became the brand; Barbara Hulanicki is Biba. Or rather she was, as it has since been taken away from her.

All subsequent relaunches of Biba, most recently by UK department store House of Fraser just this year have not been endorsed by Barbara Hulanicki, mainly because she believes they misrepresent the ethos of Biba as affordable, up to the minute fashion. She did, however, relent somewhat to design a collection of jersey mini dresses, colourful chiffon frocks and other original capsule pieces for Topshop in 2009.

What exactly is Biba though? What did it mean to the sixties? Biba broke the rules, or rather it changed the rules for young people. During a time when a young woman would still dress in the image of her mother, Biba encouraged a whole new look (at least as revolutionary as the actual Dior ‘New Look’ in 1947) of low cost, sexy, feminine separates – an entire outfit could be put together under one roof.

Colours came dark and smudgy, as per the Biba logo; Art Deco influence combined with Art Nouveau. Lots of browns and black, leopard skin prints diagonal stripes. This styling remained distinctive throughout, especially for evening wear. Barbara had a fondness for the Golden Age of Hollywood and reflected this in glamorous bias cut dresses, feather boas and flared skirts. Daytime features included puffed sleeves and high buttoned necklines. Jumpsuits, maxi coats, mini dresses and longer line skirts all proved to be popular staples.

The Biba look has since been recreated across the high street. Even now big stores look to Biba for inspiration as they recycle for a new generation. Yet more often than not modern shops misunderstand exactly what ensured Biba’s survival as a name. The aforementioned quote concerning firing staff for approaching customers is no myth. Biba concentrated on fulfilling a need for the customer, not dictating one.

Perhaps this is what Topshop and the like fail to understand? They know shoppers hate to be bothered when browsing and yet continue to do so. Biba would not do anything the customer did not want. Take the now famous communal (same sex) changing rooms, for example. These were the result of eager buyers simply desperate to try on clothes as quickly as possible. The concept stayed because it worked.

Another aspect of Biba that may struggle to find mass acceptance today is Barbara Hulanicki’s praise of thin, an ideal that comes through in the film via her beautiful fashion illustrations (one has ‘Big heads, small flat chested bodies’ scrawled next to it). Barbara is a product of her time, a time she helped define. Though if this sixties, no body, flat chested look is no longer achievable, or desirable, for most young women, then judging by the success of House of Fraser’s Biba relaunch, a significant niche is willing to subsidise them. The brand now survives as an archetype more than anything else.

The final portion of Beyond Biba deals almost exclusively with Barbara’s journey as an interior designer in Miami Beach, post-Biba but still in keeping with those Deco-esque stores she herself decorated. For those seeking primarily Biba this part of the story is predictably less exciting. And yet the clue is in the title; this is not a ‘fashion film’, more a contextualised examination of one woman’s extraordinary influence on popular culture. A legacy that Barbara Hulanicki, seemingly modest as she is, fails to truly recognise.

Beyond Biba: A Portrait of Barbara Hulanicki is available on DVD from November Films and Amazon Video On Demand, plus continues to show at selected cinemas across the UK.

© 2010 – 2014, Lord Christopher Laverty.