Sherlock Holmes Costume Guide Part 1: Frock Coats & Bustles | Clothes on Film

Featuring exclusive insight from Sherlock Holmes costume designer Jenny Beavan, we commence our sartorial analysis of Guy Ritchie’s Victorian-set mystery adventure, and with not a deerstalker in sight.

“Wear a jacket” barks Dr. Watson. “You wear a jacket!” retorts Sherlock Holmes. And he does. Watson sits down to dinner with Holmes and bride-to-be Mary Morstan wearing arguably the most unusual and interesting jacket in the entire film. It is dark blue with a stand collar and pleats across the chest. But more on that later.

Sherlock Holmes (2009) is Guy Ritchie’s re-imagining, re-boot, re-whatever of Arthur Conan Doyle’s renowned fictional detective. It’s greater fun than any of us dared hope for. Moreover the costumes by industry veteran Jenny Beavan were magnificent. Totally reinventing Holmes and Watson in the eyes of moviegoers, Beavan went to town creating a look that was period accurate in all the right places, but more importantly was truthful to the characters.

The film opens on a ‘Black Maria’ horse-drawn paddy wagon charging through darkest late Victorian London. Inside sits Dr. John Watson (Jude Law) and Police Inspector Lestrade (Eddie Marsan). Watson loads his revolver as the carriage bumps about on the cobbled streets. We cut to Sherlock Holmes (Robert Downey Jr.) making his way to their rendezvous on foot. As this tense opener unfolds, distinctive costume notes are gradually revealed.

Holmes is attired in short maroon frock coat and loose-through-the-leg grey check trousers, blue and brown block striped wool cloth waistcoat, purple cravat and white open neck shirt with unbuttoned cuffs. He encounters a heavy set thug in a double breasted dogtooth suit with DB waistcoat. A flurry of well-placed punches and a slapped ‘discombobulation’ later and Holmes had procured the man’s sizable bowler hat. Already we see Holmes as mischievous; he plays with clothes like the world is one big dressing up box.

Watson on the other hand adheres more closely to period convention. Wearing a brown check Harris Tweed high-revers lounge suit, single breasted slip-on overcoat, double stiff collar shirt with stud, Coachman’s style bowler and functional walking cane, he dresses as a gentleman that means business.

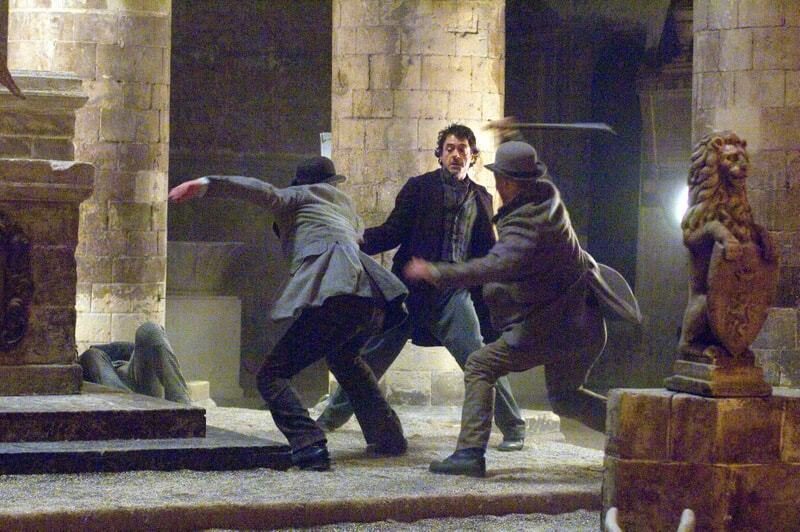

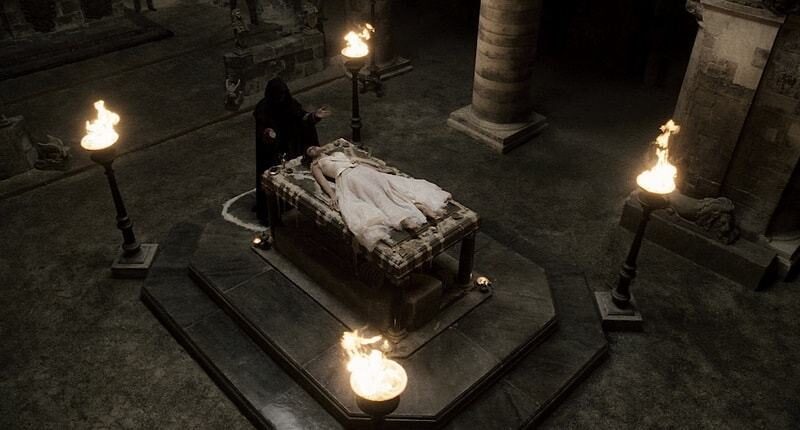

The deceptively mismatched duo meet with a handshake, then remove their hats and battle towards Lord Blackwood (Mark Strong) mere seconds before he can complete his ritual sacrifice on a catatonic young woman. Blackwood is almost entirely concealed inside a patterned purple silk cloak throughout; we can barely see his face.

Lestrade decked in long charcoal grey double breasted ‘Chesterfield’ overcoat marches onto the scene accompanied by Constable ‘Clarkey’ Clark (William Houston) and his troupe of caped ‘boys in blue’. A reporter’s flashbulb records the rescue for posterity, although Holmes awkwardly hides his face. For all his egotistical swagger and avant-garde dress, this is not a man keen to indulge fuss. For him it is about the work. Or more precisely the challenge.

Now we zip forward three months to 221B Baker Street, residence and surgery to Dr. Watson. Residence and armoury, it seems, to Sherlock Holmes. Watson chooses a correct black morning coat for examining patients. Interrupted by the thud of gunfire, he finds Holmes in his living quarters testing a homemade handgun silencer.

Housekeeper Mrs. Hudson (Geraldine James) is worried what will happen when Watson moves out following his engagement to Mary (Kelly Reilly). He reassures her that Holmes just needs another case, a suggestion that he puts to the man himself.

Dressed in, Jenny Beavan’s words, “The world’s oldest dressing gown” of ragged, barely intact paisley as acquired from London based costumers Cosprop, who were responsible for most men’s outfits sourced and created for the film, Downey Jr. slops his grumpy Holmes around the house in the manner of a bored teenager. Having not left the building for two weeks, he begrudgingly accepts an invitation by Watson to meet Mary on a restaurant date.

This is how the “Wear a jacket” line comes into play. Holmes is not a slob; he merely makes his own rules. Like discharging a firearm indoors for example. Watson just wants to make sure he does not turn up for the meal in his pyjamas.

He need not have worried. Holmes sits alone in the posh London dining hall, smartly, if a little chaotically attired in black double breasted frock coat with velvet lapels, white soft collar shirt, patterned silk waistcoat (“I never worked out whether he had ‘borrowed’ it from Watson. They kept adding in lines so I never really knew quite what was going on” attests Beavan), and blue and white striped herringbone silk scarf. Perhaps Holmes should be wearing a tail-coat rather than frock for the evening, though he has clearly made some effort for Watson.

Mary arrives arm-in-arm with Watson wearing a navy blue velvet and light blue silk dress enclosed with white lace gathered into bodice with low v-neckline. Kelly Reilly’s genuine 19th-century diamond necklace was provided for filming by Martin Travis of Symbolic & Chase, Bond Street. As Holmes correctly deduces, it was on loan from Mary’s grateful employer.

Jenny Beavan’s choice of dinner attire for Jude Law has provoked considerable hypothesising. His long blue wool coat is only briefly glimpsed, yet mainly because of the front pleats it stands out as highly distinctive.

Those who surmounted it was military in origin were not wrong. It was worn by medical officers during the Second Anglo-Afghan War; Beavan confirms that she chose this particular coat because, “I was trying to emphasise Watson’s military side; it is just one of the most elegant pieces of uniform. I checked with an expert and he said it was fine”. The coat is actually the longer, ceremonial version of Blues Patrol, a dark blue formal tunic that could be worn for dress and ‘walking out’. It is still in use today. Although commissioned by Cosprop, this particular coat was made by Karen Smith who is head tailor for South Bank’s National Theatre in London.

The officer’s tunic provided Law with a distinction in outfits away from those omnipresent tweed suits, while also hinting at Watson’s past in the armed forces. Choosing such an item for dining would have been perfectly acceptable for a man in his position. Moreover, as Holmes proudly reminds us and Mary, Watson is a war hero.

The meal itself does not go well. Holmes manages to insult Mary within five minutes of meeting her. She slaps his face and strides out closely followed by Watson, who we almost feel pities his imprudent, self-destructive best friend.

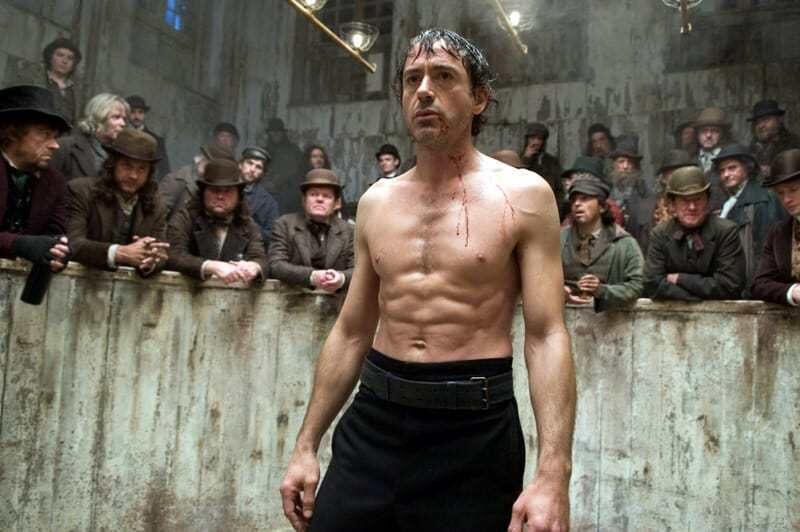

Holmes works off his frustration by partaking in a bare knuckle boxing match. Shirtless, he wears relaxed high-waisted black trousers, a style briefly popular in the late 1800s. His big belt is perhaps a historical indulgence, yet may have been worn by blue-collar workers. One would imagine this is how Holmes sees himself, as not belonging to either class but rather an anarchic mixture of both.

The following day Watson unearths Holmes at the Punchbowl Inn. Typical for Watson, he is spotless in grey and red striped Harris Tweed lounge suit featuring slanted ticket pocket with white rounded collar shirt, black four-in-hand necktie and that same slip-on overcoat. Enjoying the odd clothing rebellion, he sports his brown coachman’s bowler at a jaunty angle. Holmes is in a voluminous and now soiled white shirt.

Travelling with Holmes as Lord Blackwood’s “last request” before execution, Watson protests the ownership of a sharp silk waistcoat worn the previous evening. There were six different waistcoat patterns for Robert Downey Jr. with multiples in various colours. Check Jude Law’s mischievous expression after his character first punches Holmes and then tosses the aforementioned waistcoat out of the carriage; Watson clearly enjoys their little spats.

Outside the prison a busy street scene is painted vividly: tweed flat caps on manual workers, bustles and corsets for society ladies, policemen in heavy belted tunics, coachmen ominous figures in black Ulster cape coats. Some wonderfully familiar costume design for the period, although Beavan insists that well-chosen extras with characterful faces help her job immensely.

Meeting Blackwood again, Holmes wears his evening frock coat with the velvet lapels; his baggy shirt scrunched awkwardly underneath. Blackwood is buttoned tight in white thinly striped wing collar shirt with pleated front, black necktie and jet stud, and textured leather waistcoat in Autumnal colours with beaded watch-chain. He is clean, no dirt on him. Seemingly in control of his own destiny, Blackwood informs Holmes that “Three more will die” before the otherworldly plans he has set in motion are complete. Naturally Holmes is dismissive.

A short while later and Blackwood is dropped via the hangman’s noose, then pronounced dead by Watson. It was unusual of the authorities to hang Blackwood in his own clothes, that full length leather coat especially. As an aside, the ‘white’ on the soles of Blackwood’s footwear which gives them the appearance of PVC Wellington boots is likely a light reflection. Beavan confirms they would have been either plain black or leather.

Seemingly case closed, Holmes returns to his bored, sedentary lifestyle. Refashioning that ancient dressing gown as a balled-up pillow on the floor, he is jolted awake by the sound of nuts cracking. Irene Adler (Rachel McAdams) sits in his quarters preparing an exotic brunch.

She wears an ornate big bustle ‘visiting dress’ in vibrant pink satin with upturned collar and hat. The dress is a spot-on accurate pattern for the time. The colour is riotous, marking Adler out as a Victorian lady unlike any other in the story. A previous romantic relationship is intonated, as are Adler’s criminal tendencies. The 47 carat fancy yellow diamond Holmes implies she stole from the Maharaja was also provided by Symbolic & Chase.

Holmes feigns nonchalance but clearly still has strong feelings for her. The moment Adler departs, he tails her to a waiting carriage. At this point in familiar Guy Ritchie style the story cross-cuts between Watson and Holmes discussing Adler’s return and a flashback detailing his efforts to follow her through Baker Street.

Watson sits engrossed, his stiff collar removed. With both feet up, he reveals front-laced Balmoral half-boots. These particular boots are rather cumbersome for a professional man in late 19th century, again intimating at his quiet tough guy persona. Holmes parades around explaining his actions wearing a typically ample (and grubby) white linen shirt, brown and black thick striped braces, and trousers with satin tape trim running along the outside leg; usually chosen as a formal evening garment the tape was then an experimental twist.

A flashback unfolds: Holmes grabs his own gold silk scarf (initially worn around his neck, later the waist), then procures Watson’s lightweight slip-on (which curiously seems to gain a couple of sizes on Holmes) before enhancing his disguise with plaid wool scarf, crumpled top hat and an eye patch. Helpful then that Adler cuts through a street circus, as Holmes can blend right in with the freakish crowd.

As he pulls a ruse to peep inside Adler’s carriage, Holmes catches the merest glimpse of the top hat, cape coat and black leather gloves worn by her patron. We can all guess who he is, yet for now Ritchie hides this nefarious villain behind his voice (which incidentally sounds a lot like actor James Fox playing Sir Thomas in the film). Holmes remains unmasked by Adler and her mysterious employer, though narrowly avoids a bullet in the cheek from the man’s unique hidden pistol.

For Adler’s innovative, floral embossed satin coat, Jenny Beavan insists she cannot remember exactly where the idea originated from; it was a combination of influences that came together on her “mood boards”. The coat’s wide sleeves, along with the dress’ huge bustle, were initially designed to house the pocket knife Adler pulls on two muggers. Apparently the stunt performer had all kinds of ideas for the costume then changed his mind. Her velvet upturned brim hat stuffed with colourful silk flower blooms may look extravagant, but for a lady with means it was fairly typical.

Watson, despite his impending retirement as Holmes’ sidekick, is clearly captivated by the yarn. At that moment the duo are paid an impromptu visit by Constable Clark, very serious and smart in his Police uniform tunic with cape attached via gilt chain (surely a throttling risk? Perhaps why it was later removed?). Justifiably hesitant, he informs both men that Lord Blackwood has seemingly “risen from the grave”. A brief glance is shared. Holmes is intrigued. The game is afoot.

With thanks to Jenny Beavan.

© 2010 – 2014, Lord Christopher Laverty.