Brave: Costume in Animation – Interview with Claudia Chung | Clothes on Film

With the release of Disney/Pixar’s latest adventure Brave (directed by Brenda Chapman and Mark Andrews); featuring colourful tartan cloaks and the Tudor-esque dresses of its heroine Merida (voiced by Kelly Macdonald), it is worth considering exactly what role costume plays in animated film. Does this craft even exist for animation?

Clothes on Film talk exclusively to simulation supervisor for Brave, Claudia Chung, about this process and whether or not costume truly has a viable, practical function outside of live action cinema:

Educated at University of California-Berkeley, Claudia Chung joined Pixar in 2002 after interning for summer in 2001. Her first role was as rendering technical director on Finding Nemo (2003), progressing to simulation and rendering technical director for The Incredibles (2004) and Ratatouille (2007), then as cloth lead on Up (2009). For Brave, her role was to oversee all aspects of grooming, costuming and shot simulation.

MILD SPOILERS

Clothes on Film: What is the current process for costume design in animated film? How has it changed?

Claudia Chung: It’s interesting; I think it’s changed a lot over the years. I’ll start with what it is now. Basically, at Pixar, what we do is model the garments in 3D and then we have a proprietary software we use to essentially sew them all together. The reason we still have the sewing process even though we model in 3D is because we can mesh the model in a way that the simulator is happier with. There are sometimes features like the frills on Merida’s dress or her sleeves; we wanted to use the traditional techniques of gathering so we still “sewed” them on.

The last step is the fitting process, where we lay the garment on the character as if you were trying on a suit and make her walk or do some kind of motion, just to see how it fits, how it lays, and then go back to the original 3D model and make any changes. At Pixar, which may or may not be different for other studios, we still flatten the meshes into 2D texture. That 2D pattern is what we send to the simulator. This way the simulator understands the grain direction of the cloth which is very important to represent sewing in real life. Especially with things like dresses or pants; the way they hang off the body matters and we can really see the difference by doing it this way.

When it came to the kilts we kind of used the same technique, but there’s no pattern because it’s tartan so we had to use more of a draping process. It was a much more complicated 3D model. If you saw it, it looked like a strange accordion Origami-folded thing, but when the simulator took over and placed it on the character it looked like a real tartan, so it maintained the flatness that the fabric would have but since we’re moulding in 3D we had to create the folds manually.

Bringing Costumes to Life for Brave: 1) Sketch artists take their cue from story and personality traits to define what a specific garment will look like – seam details are not included at this point. 2) A simulation artist builds a 3D model of the garment in the computer based on these artist drawings. Functional details, e.g. seams and pleats are now built in as separate pieces. The dress is then ‘sewn’ in the computer.

CoF: The kilts must have been incredibly difficult to fit because they contain several yards of fabric to conceal?

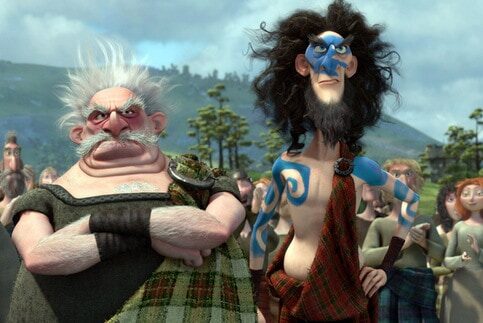

CC: Some of the tricks we employed… we actually broke the kilt into different pieces. It is definitely, like, 8 or 9 yards of fabric. Just for the skirt itself, for Fergus, I think it’s about 7 yards of material that is folded around his waist. The skirt was actually pretty trivial to do compared to the rest of the kilt. The big challenge there was to make sure it didn’t look like a toga or cheerleading skirt. The pleats and all those things had to look right. But what went over the chest and what drapes on the side of his waist… these are actually separate pieces that we sewed together afterwards so we could have control of all the folds. Areas like the belt or the brooch on his chest hide the seams that we are putting in. There really is no way that we could fold in 9 yards of fabric underneath that brooch, so it is a little bit fake.

CoF: With all the layers on Fergus he must have been tough to costume?

CC: He has 8 layers of clothing, and it’s more than we’ve ever done before. I remember seeing the initial artwork for Fergus and going “oh my gosh, how are we going to do this?” Before this, probably the most complex things we did were the chefs’ costumes in Ratatouille, and that was because they had an apron. The approach with Fergus was just walk by walk – build the chainmail, build the tunic, build all the pieces together and then slowly work our way up. The folds across the chest are essentially 16 layers. When it comes to simulations most cloth simulations in a computer hate layering. It’s a bad thing; very unstable.

CoF: Was there ever any discussion of hiring a live action costume designer for the film from the CDG (Costume Designers Guild)?

CC: Well, we did back on The Incredibles. In the beginning, all we knew how to do was model in 3D. The Incredibles was the first movie where we really started to have humans. We did employ a tailor/costume designer. It was really helpful but at the same time we realised that because we work in the computer, the concepts help but the process doesn’t. It doesn’t actually translate. In real-life costume design you have a lot of tricks for the tools you have, but these are not the tools you have in a computer. Many times in a computer it is a lot easier. I can just press ‘undo’ if I’ve made a mistake – I don’t have to spend time unpicking seams. We had our costume designer for a little bit but in the end we realised we’d got the foundation and could build upon that.

3) While ‘tailors’ within the simulation department build a garment model, the shading director considers possible textures and colours. As Brave is set in ancient Scotland, fabrics available were limited to linens and wools. 4) When the 3D model of a garment is ‘sewn’, a character must ‘try it on’. Being as this is not physically possible it must be built around the character within the computer as individual pieces.

From The Incredibles to Up we did traditional 2D pattern-making, but the iteration process was so slow we switched back to modelling in 3D. All our tailors do take actual sewing classes. My background for example is computer science. When I started tailoring within a computer it looked terrible. I had no idea how to sew a pair of pants. I think I spent a month sewing a pair of pants in Ratatouille and my lead said to me “Claudia, maybe we should get you into a sewing class.” And when I took my sewing class they had me working on tablecloths. It really helped because when you’re in a sewing class you really understand the 2D to 3D form. In pattern-making, a negative space and positive space are very important, but all of our tailors now understand those concepts.

CoF: Do you think that costume design in animation will become a separate job title as technology becomes even more advanced, or do you think it will always fall under your banner as simulation supervisor?

CC: Even though on Brave we had simulation as the main department, our tailors do have their own identity. They think of themselves as tailors. If you look at the way we credit them, we credit them as tailors or simulation artists. What I have noticed over the last 10 years is that more and more people are choosing tailoring or simulation as a discipline which is not something that happened when I got into animation at all. It’s not something that existed. I’m hoping even more people become interested after Brave. Now you see the artistic side of it; it’s no longer just physics or simulation, there’s more art to it now.

5) A shading artist adds final textures and colours to the garment. For Merida’s informal day dress, a tightly woven linen look was chosen in a rich blue allowing her to move easily. Her formal dress is lighter blue and decorated with jewels. It is deliberately constricting to imply her mother’s influence. 6) New for Brave, a shading technique was introduced of weaving threads of fabric within a computer program. This allowed the artists to adjust tightness of cloth and add fraying to garment edges and hems.

CoF: On Brave, how much was costume dictated by the character and how much by technical limitations? Fergus springs to mind…

CC: A lot of times with our main characters like Merida and Fergus we don’t negotiate with the art director that much because they are main characters, and every aspect of design has an intent to support who that character is. With Fergus, if we were to negotiate, it would have been “does he really need the bear cloak?” We couldn’t say he doesn’t have a kilt on, there was no way we could put him in something else, so that was a necessary challenge that we had to take on. When it came to chainmail and especially the bear cloak we would broach the subject and immediately it was cleared up. He has to have the bear cloak because he is head of the bear clan. And the boots as well; that’s part of who he is. The director was very keen that he was a warrior and that’s why he needed the chainmail. He has lots of things hanging off him as well, like the scabbard. One thing we did negotiate on was the strap that he has across his chest. That was great because it actually held the kilt in place so it gave us more control, but that strap is actually traditionally where the scabbard should hang from. However, that would have been incredibly difficult, because then you have a very heavy thing hanging down, so the director was perfectly happy with us moving it down to his belt which also hid the scene connections. We know that if anyone was really into this thing they’d be saying “why isn’t the scabbard on his chest?!” It was never a question of “can we not have the sword?” it was just “can we move it somewhere else?”

CoF: How many of the costumes did you actually make up in real life and was this of any benefit to you?

CC: When we started on Brave we realised it was a very different challenge. We don’t wear kilts, we don’t wear dresses all the time, we’re not wearing cloaks and we’re not running around with swords or bows and arrows, so it is actually super helpful to know how these things move and drape. We tried to do a lot of references from movies that we’d watched, but in the end the most useful thing was to have tactile costumes that we could play with, understand and feel the weight of.

A good example of this was Elinor’s dress. She had these crazy big, swinging sleeves. We would do all the animation as normal, as if she was wearing a t shirt, but when we came to simulate the sleeves you wouldn’t see any of the animation. It was a bit like her wearing a skirt on her arms. Any animation we did, her hands would be covered. We actually built a real mock version of Elinor’s sleeve and handed it to animations so they could see how it moved. There is a scene where Elinor plays with the chess pieces and in this key scene she has to hold the sleeves back or else in real life they would clean the board. We try as much as we can to make things realistic. Yes, her hand is there, but we have to guide the sleeves to make sure she doesn’t knock the chess pieces over. I think this actually does make this more believable.

Creating Kilts: The art department purchased tartan samples on a scouting trip to Scotland in order to study weave, weight and texture. To wear a traditional kilt a person must lie on the ground and have nine yards of tartan secured to their body with a belt holding the folds and Celtic (penannular) brooch securing it to their shoulder. The simulation department learned how to drape tartan on an actual mannequin (torso) and then transferred this to a computer model in sections, establishing each fold of the kilt separately so it was easier to manage. It was then ‘sewn’ together to resemble one strip of continuous tartan.

CoF: Who was the toughest character you worked on for Brave? The fibres of Merida’s dress looked very detailed in close-up.

CC: In the character department they created this amazing loom technology that essentially weaves every strand of fabric into the shader so it has the texture of real wool. It gave us a very tactile quality that looks so real and you want to touch it. When it came to building and tailoring Merida’s dresses her challenge is that she wasn’t a classic animated female body; she actually has really wide hips and really strong arms so we had to make her look strong but still feel feminine. So when it comes to designing dresses like that it’s really key to where the dress hangs from the hips and how tight it is around the arms.

As we were working with the art department there were ongoing discussions. For example, with her light blue dress (formal dress), the one that she rips, that dress had 4 stages. When we were creating the fully-destroyed version of the dress it was fascinating to watch the art director. He explained that all the tears on that dress point to her core, her heart. It’s a subtle thing but his design is such that he always wanted it to draw to her heart. Look at the tears – they are all pointing at her.

With thanks for Claudia Chung.

Brave is currently on general release.

You can watch The Incredibles at LOVEFiLM.com.

© 2012 – 2014, Lord Christopher Laverty.